When I was a child my father advised me that when visiting a barbershop, one should always pick the oldest barber. That made sense: the one who had learned from two generations of elders, had seen trends fly by, had weathered every bizarre request, could find the simplest and most elegant solution to any problem. And so it is with editors: If you are ever given the choice (you seldom will be, alas), go with the oldest editor. In addition to all the credentials of the oldest barber, the oldest editor will also know that every serious writer has a personality that comes through in the work, and that the editor’s job is to preserve and improve that voice. Younger editors—most of them, now that older editors have been put out to pasture—often have a burning desire to carve their initials in the work of others.

Sometimes it’s not their fault, really. Increasing corporate oversight may be to blame. Even if algorithms aren’t being chased, every outlet with pretensions to stature will attempt to create a house style, and that will entail editing their stable of writers so that they all sound alike. Younger editors, who for one thing want to keep their jobs, will become enforcers. And it’s much easier to edit to a formula—to edit from the outside—than to get all the way inside the work and edit from there. Mechanical editing smoothes the surface, trimming digressions, expunging authorial tics, neutering interesting anomalies, turning novel phrases into the clichés they were constructed to avoid. It is as if everything were destined for the tired-businessman market, the people for whom AI summaries are intended. It represents an invisible form of dumbing-down. Anyway, some of these practices have been common among certain breeds of young editor going back to when magazines lived on advertising and were owned by hands-off millionaires who merely wanted to burnish their biographies. It’s just easier for the editor whose mind is on a thousand other matters.

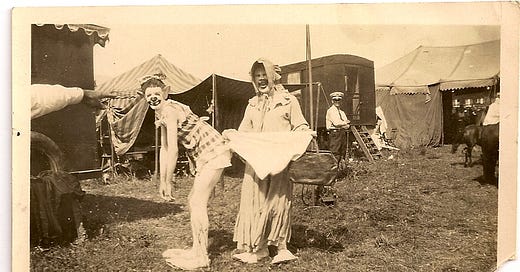

I was formed by a great editor, Barbara Epstein at the New York Review of Books, who when I worked as her assistant showed me every day how editing is done. A bit later I was lucky to meet the excellent Duncan Stalker, who edited me at Manhattan, inc., the New York Observer, Vogue, and perhaps other places I’ve forgotten. (Duncan died of AIDS in 1991.) And I’ve had good but briefer experiences with many others. I’ve seen scores of editors go by in my 40+-year career. I’ve needed the money and I’ve been a soldier. I’ve had screaming matches now and then but have almost never pulled a piece. (One of the only pieces I ever pulled was, weirdly, from Barbara at the NYRB. It was a review of Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces, and she and I were talking past each other, not about style but about substance. At some point I realized that when she used the word “culture,” Barbara meant Auden, Stravinsky, Balanchine, while I used it to refer to hot-dog stands, bus stations, shooting galleries.)

Note that I’m talking exclusively about magazines here. My experiences with book editors have been entirely different. I’ve only had five or six altogether, so my sample is limited, but in every case their hands have been extremely light. (One of them, who edited just one book of mine, left not a single mark on the manuscript. I wished I’d had the foresight, in those analog days, to put some pages in upside-down, to see if they were still that way when I got the manuscript back.) My books have generally been published exactly as I wrote them. In recent years, book publishers have (at long last) begun fact-checking. That is quite a departure from the days when, challenged for a source by a magazine fact-checker, I quoted from my own previously-published book, and that was accepted despite the book itself never being fact-checked.

The care and feeding of editors is a complex matter and should not be undertaken lightly. If it is possible to bond with your editor, do so—be upbeat and chatty in your email correspondence, turn copy in early if possible, agree to everything that won’t break your spirit. That is because the value of editors, absent any other, lies in their consistency. That is much like critics, at least back in the day when critics held their posts for a while; you’d get to know their tastes and inclinations and blind spots and irrational enthusiasms, and decide whether to see the picture by triangulating among those. Similarly, once you have figured out the boundaries of your editor’s knowledge, taste, prejudices, gumption, and vulnerability, you can adjust your writing to suit. You learn evasive action and camouflage. You buddy up so hard with your editor that they become afraid to offend. With a mediocre editor, this is simply a game. With a great editor, the tables are reversed. They come to live inside your head. Barbara died nineteen years ago, but she appears inside me every time I sit down to write. She notices every solecism, every inconsistency, every received phrase, and is always urging me to unpack and clarify. But even with a dull editor the goal is the same: to pre-edit the work so that there is very little left for the editor to say.

A note on deadlines: there are at least three, depending on the publication. The stated deadline is a scarecrow; honor it if you’re trying to make nice, but it doesn’t really mean anything. The second deadline is, more or less, the real one for most people, and comes a week or so after the first. The third deadline is the last possible point for copy to be processed before the figurative presses roll. That is the VIP parking of the author-editor relationship, and it may take you some time to work up to it. In general you should try to make the scarecrow deadline for the first four or five pieces you write for that editor. After that you can park in number two, unglamorous but nevertheless assigned. When I found all this out I felt like I’d been handed the secret menu at Rao’s.

Lucy, I love the analogy (is that the right word? Stage fright here) about choosing the oldest barber. I tried a new salon and booked with the owner/manager who looked to be in his 70s -great, I thought, he'll have learned to cut hair in the late 60s/early 70s when the shag was invented. "Why did you choose me?" he said, just as he was cutting my bangs, his scissor hand trembling slightly, the scissors aiming right towards my eyes! And I thought "shit - he's getting TOO OLD to be doing this, and he knows it but he's not going to be the one to say anything." Thankfully writing and editing isn't physical work. Thank you so much for your posts, I relish and learn from every single one. signed, the granddaughter of an Italian barber

great advice, i have applied to a mentorship program for my poetry and will see if i can adapt it it for that.... thanks.